The AI revolution has a power problem, and Silicon Valley thinks the solution might be floating 250 miles above our heads. As data centers strain electricity grids and guzzle billions of gallons of water for cooling, a surprising number of tech companies are looking upward; literally, for their next computing frontier.

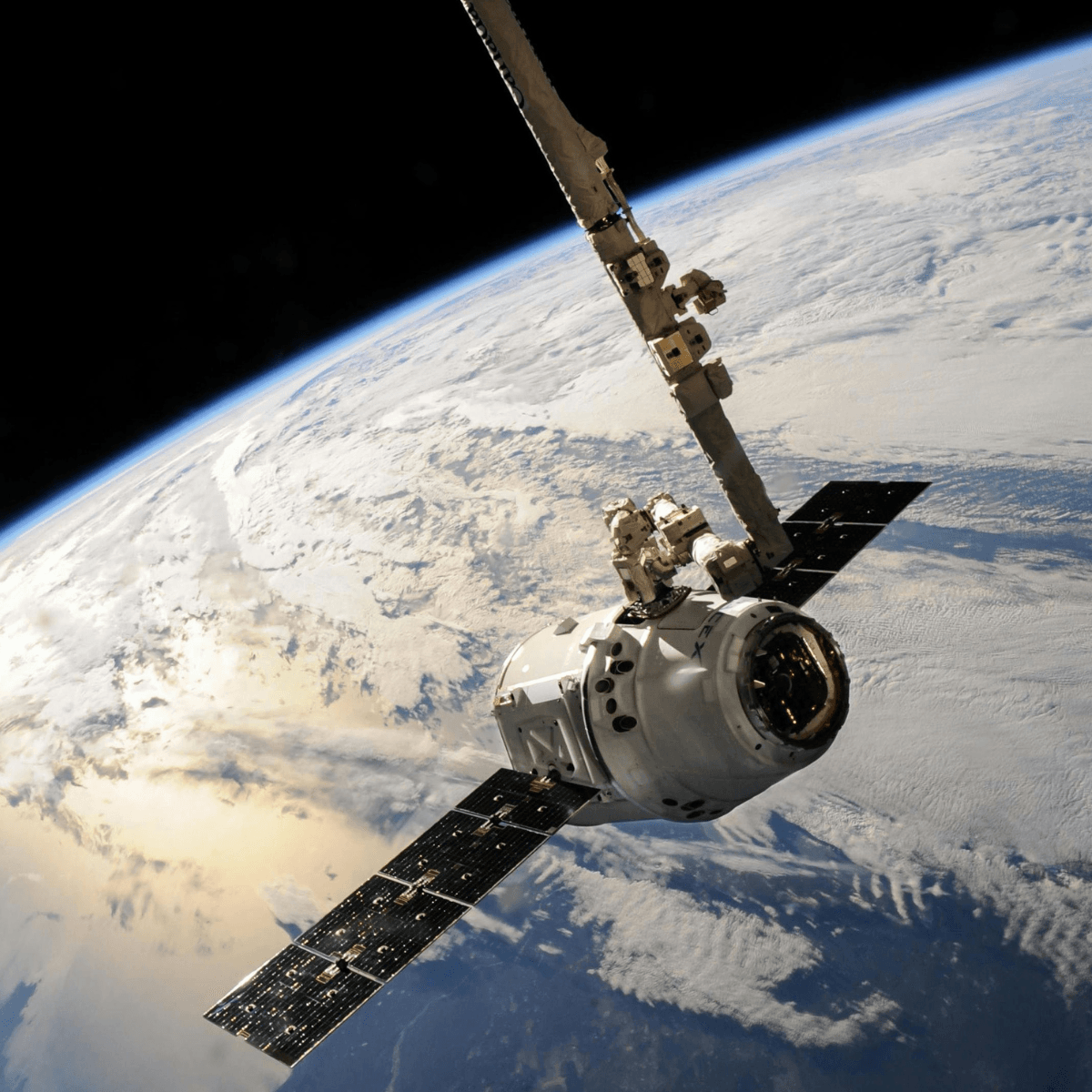

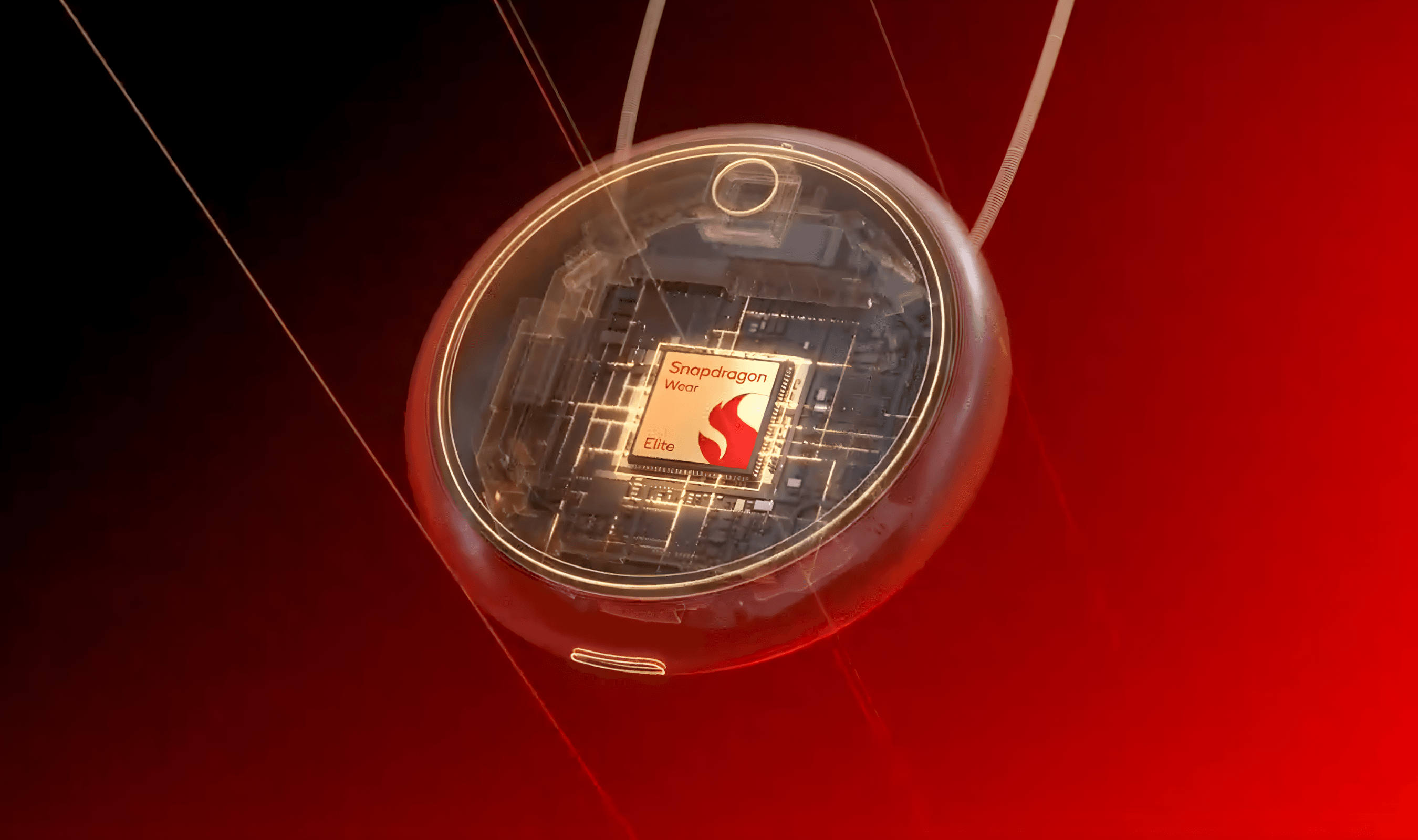

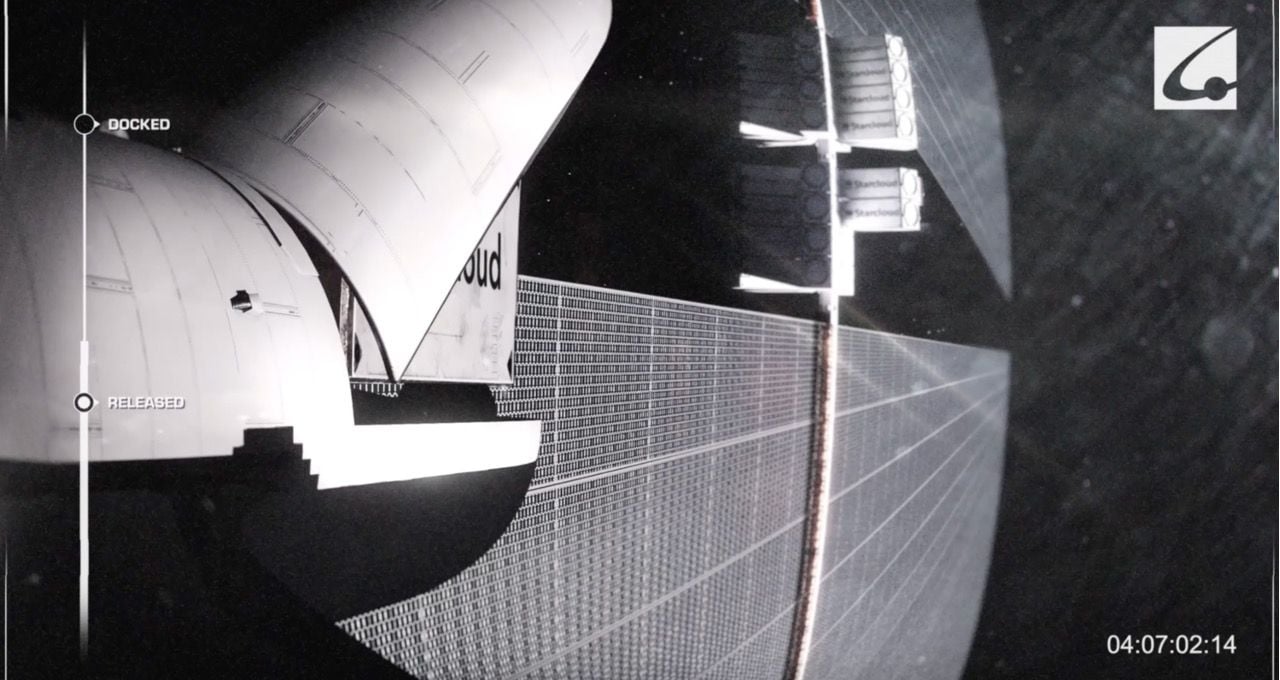

In early November, Google unveiled Project Suncatcher, an ambitious plan to launch an 81-satellite constellation into low Earth orbit by 2027. The goal? To harvest constant solar energy for AI processing, free from Earth's pesky day-night cycles and weather patterns. Meanwhile, Nvidia-backed startup Starcloud just made history by training an AI model in space for the first time, running Google's Gemma language model on an H100 GPU that hitched a ride on a SpaceX rocket in November.

The numbers are getting real. Data centers already consume about 4% of U.S. electricity, and projections suggest that could jump to 12% by 2028. When you factor in AI's voracious appetite - Goldman Sachs predicts data center power demand will increase 165% by 2030, you start to understand why companies are considering such radical solutions.

Unlimited Power, Natural Cooling

The appeal of orbital data centers boils down to two fundamental advantages: energy and cooling. In space, solar panels operate in near-perfect conditions, generating electricity 24/7 without interruption from clouds or nighttime. Starcloud CEO Philip Johnston puts it bluntly: "In space, you get almost unlimited, low-cost renewable energy."

Then there's the cooling problem. Terrestrial data centers can use up to 5 million gallons of water per day for evaporative cooling. In orbit, you simply radiate waste heat into the vacuum of space, no water required. Johnston claims his company's orbital approach could achieve 10 times lower carbon emissions compared to land-based facilities powered by natural gas, even after accounting for launch emissions.

But the space-based approach isn't just about being green. There's a security angle too. Steve Eisele, president of lunar data storage company Lonestar, points out that putting data on the moon makes it "way harder to penetrate; it's above any issues on Earth, from power outages to war." His company has signed a $120 million deal to build six data-storage satellites, with the first prototype heading to the International Space Station soon.

The Economics of Escape Velocity

Of course, launching anything into space isn't cheap, and that's where the business case gets tricky. Google's Suncatcher team estimates that launch costs would need to fall to under $200 per kilogram by mid-2030s for their vision to make economic sense. Currently, SpaceX's Falcon 9 launches cost around $2,500 per kilogram, a huge gap that needs closing.

The European Union is taking a more cautious approach through its ASCEND project, which commissioned Thales Alenia Space to study the feasibility of space-based data centers. Their roadmap calls for a 50-kilowatt proof of concept by 2031, eventually scaling to a 1-gigawatt deployment by 2050. The study suggests such systems could offer "a more eco-friendly and sovereign solution for hosting and processing data" while aligning with Europe's 2050 carbon neutrality goals.

China isn't sitting this one out either. In May, they launched 12 satellites for what they're calling the Xingshidai "space data center" constellation - the first of a proposed 2,800-satellite fleet designed to process data in orbit.

For all the orbital enthusiasm, there are some very earthly realities to consider. Google simultaneously announced a $40 billion investment in Texas data centers, suggesting orbital infrastructure remains supplementary rather than a replacement strategy. And emissions rose 51% at Google amid these announcements, highlighting the tension between ambitious space projects and immediate terrestrial impacts.

Space debris presents another major hurdle. As one space scientist noted, Google's proposed constellation will need to navigate an orbit already crowded with thousands of tracked objects and millions more too small to monitor effectively. In just the first six months of 2025, SpaceX's Starlink constellation performed 144,404 collision-avoidance maneuvers.

Then there's the question of whether we're just pushing environmental problems out of sight. Rockets release pollutants at higher altitudes where they last longer, and the ASCEND study found that space data centers would only reduce emissions if launchers emitted 10 times less carbon than current models.

What Comes Next

The next few years will be telling. Starcloud plans to launch increasingly powerful satellites each year until reaching gigawatt scale. Axiom Space intends to test prototype servers on the International Space Station. And Lonestar's lunar data storage experiment, while only lasting a couple of weeks before lunar night descends, will test practicalities like secure data transfer protocols.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has predicted space-based solar data centers will become cost-effective within 20 years. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman told a podcast audience that "a lot of the world gets covered in data centers over time," and his company is part of the consortium behind the $500 billion Stargate project.

The bottom line? Whether orbital data centers represent a clever solution to AI's energy crisis or just an expensive way to push problems out of sight, one thing's clear: the race to build computing infrastructure beyond Earth's atmosphere is officially heating up. And as data center electricity consumption is projected to more than double by 2030, that race might just be getting started.