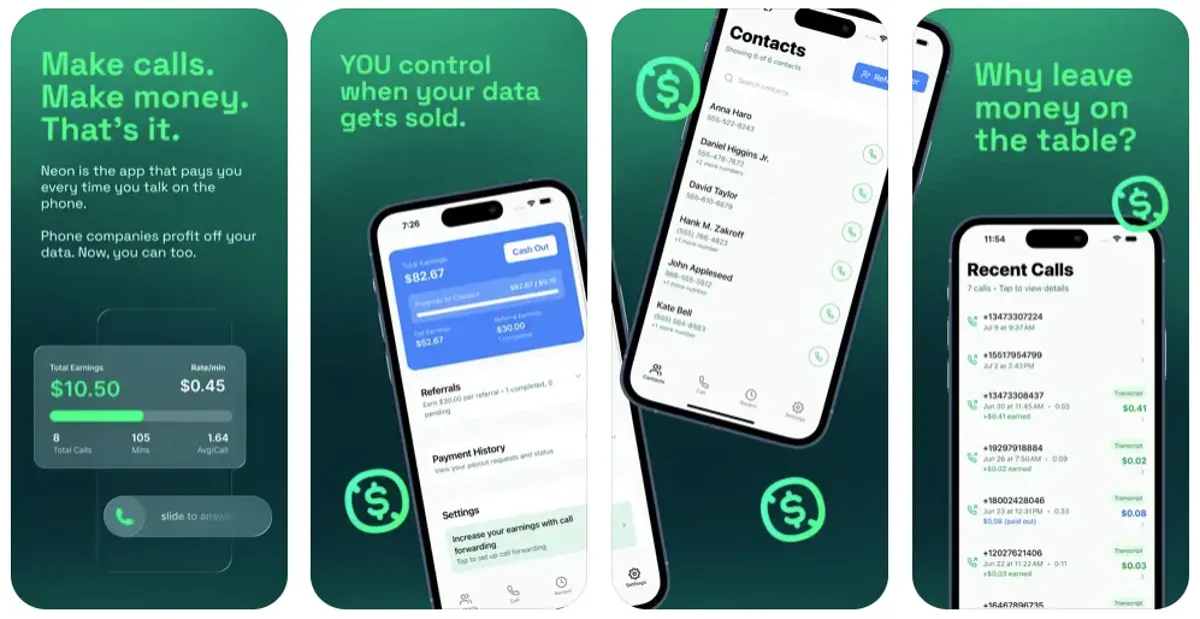

Neon Mobile briefly climbed Apple's App Store charts in late September 2025, but went offline on September 25, 2025 after reaching No. 2 in Apple's App Store Social Networking category on September 24, 2025. The app had a simple pitch that should make everyone's skin crawl: record your phone calls and we'll pay you for the privilege. What could possibly go wrong?

You can also set us as a preferred source in Google Search/News by clicking the button.

The app promises users "hundreds or even thousands of dollars per year" in exchange for audio conversations - $0.30 per minute when calling other Neon users (Neon lists $0.15/min when calling non-users), and up to $30 per day. It's surveillance capitalism distilled into its purest, most nauseating form: companies paying pennies while users hand over the most intimate details of their lives.

But Neon isn't some rogue operation. It's the inevitable result of a business model that Harvard Business School professor emerita Shoshana Zuboff has been warning about for years. In her research on surveillance capitalism, she describes how companies capture "surplus behavioral data" beyond what's needed for services, then package it as "prediction products" sold to business customers interested in knowing "what we will do now, soon, and later."

According to The Federal Trade Commission, which documented this explosion of data harvesting in a September 2024 staff report, major social media and video streaming companies "engaged in vast surveillance of consumers" to monetize personal information while failing to protect users. The companies could "indefinitely retain troves of data" from both users and non-users, often sharing it broadly with insufficient oversight.

What makes Neon particularly disturbing is how brazenly it markets this extraction. While traditional tech giants at least pretend their data collection serves user convenience, Neon drops the pretense entirely. According to its terms of service, the company grants itself a "worldwide, exclusive, irrevocable, transferable, royalty-free" license to sell users' recordings to "AI companies" for developing and training machine learning models.

See also - Oracle Stock Crashes 16% from Peak - Is the AI Bubble Finally Bursting?

This represents something far more insidious than typical social media surveillance. Voice data contains biometric identifiers that could enable sophisticated fraud. As cybersecurity attorney Peter Jackson warns,

"Once your voice is over there, it can be used for fraud... they have recordings of your voice, which could be used to create an impersonation of you and do all sorts of fraud."

The rise of apps like Neon reflects how AI has fundamentally shifted data economics. Where companies once collected information primarily for advertising, AI training has created new markets for raw human input. Stanford researchers Jennifer King and Caroline Meinhardt note that AI systems pose privacy risks beyond traditional data collection, particularly when personal information gets "repurposed for training AI systems, often without our knowledge or consent."

See also - Everything Google Knows About You (And How to Stop It)

What's perhaps most telling is that Neon's approach appears technically legal. Privacy attorney Jennifer Daniels explains that recording only one side of conversations is "aimed at avoiding wiretap laws" in states requiring two-party consent. It's a loophole that highlights how existing privacy frameworks haven't kept pace with AI's appetite for data.

The app's rapid ascent to No. 2 in social networking reveals something depressing about consumer psychology. Early analyses of Apple's App Tracking Transparency found that most U.S. users declined tracking when presented with a clear opt-in prompt (e.g., Flurry estimated 96% opted out in May 2021). Yet here's an app explicitly monetizing surveillance, and users are flocking to it. There's reportedly enough demand that some people now view data extraction as inevitable - if their information is being sold anyway, they might as well profit from it.

This cynical calculation misses the broader implications. Neon doesn't just compromise individual privacy; it puts everyone in users' contact lists at risk. Neon says it records only its user's side unless both parties use Neon; if both are Neon users, both sides may be recorded. It's surveillance by proxy, turning users into unwitting data collection agents.

See also - Your Phone Already Knows Your Age, It Just Isn't Telling You

The business model also reveals how AI companies are solving their training data problems. Rather than relying solely on publicly available information or expensive licensing deals, they're creating economic incentives for users to directly feed personal data into their systems. It's crowdsourced surveillance disguised as a side hustle.

Congressional lawmakers have recognized these dynamics. Representatives Anna Eshoo, Jan Schakowsky, and Senators Ron Wyden and Cory Booker introduced the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act precisely to target business models that profit from "the unseemly collection and hoarding of personal data." The legislation aims to remove financial incentives for companies to exploit consumers' personal information.

But regulatory responses lag behind technological innovation. While California's Consumer Privacy Act and similar state laws create some protections, they're designed for an earlier era of data collection. The emergence of apps like Neon suggests we need frameworks specifically addressing AI training data and the economic incentives driving its collection.

The broader concern is what this normalization of paid surveillance means for society. When privacy becomes a luxury good - something only those who can afford to decline payment can maintain - we're creating a two-tiered system where economic desperation drives data extraction.

See also - Why AI Safety Officials Keep Quitting Their Jobs

Neon represents the logical endpoint of surveillance capitalism: cutting out the middleman of useful services and paying users directly to become data extraction points. It's brutally honest about what many tech companies do more subtly - turn human experience into raw material for corporate profit.

The app's success suggests we're crossing a threshold where privacy invasion becomes openly transactional. What was once hidden behind terms of service and user agreements is now explicit: your conversations have market value, and companies are willing to pay for them. The only question is whether we'll collectively decide some things shouldn't be for sale.

If you enjoyed this guide, follow us for more.